When a society’s main way of communicating changes, the culture changes with it. The shift from oral storytelling to writing reorganized how people made and judged ideas. As Eric Havelock notes, orality tends to place ideas side by side (parataxis), while writing lets us order and rank them (hypotaxis). Later, the internet unsettled those hierarchies by putting everything in the same feed. Now generative AI pushes a new turn: instead of going out to find information, we ask a model to synthesize it for us in real time.

The shift from a largely static print culture (books, journals, newspapers) to the dynamic, hyperlink-laced world of the internet (posts, tweets, comments, videos, remixes) is instructive. If print stabilized hypotaxis—codified hierarchies of knowledge—the internet reintroduced powerful currents of parataxis, the flattening of ideas. Feeds place headlines, memes, and research side by side; comments appear co-present with reported stories; search results level institutions and hobby blogs into a single scroll. The effect isn’t a simple “reversion” to orality, but a hybrid: an always-on, text-heavy environment that nonetheless rewards immediacy, performance, and identity signals. We might call this the era of networked parataxis or feed culture. Authority did not vanish, but it was continuously jostled—ranked, re-ranked, and sometimes drowned—by the drumbeat of the new.

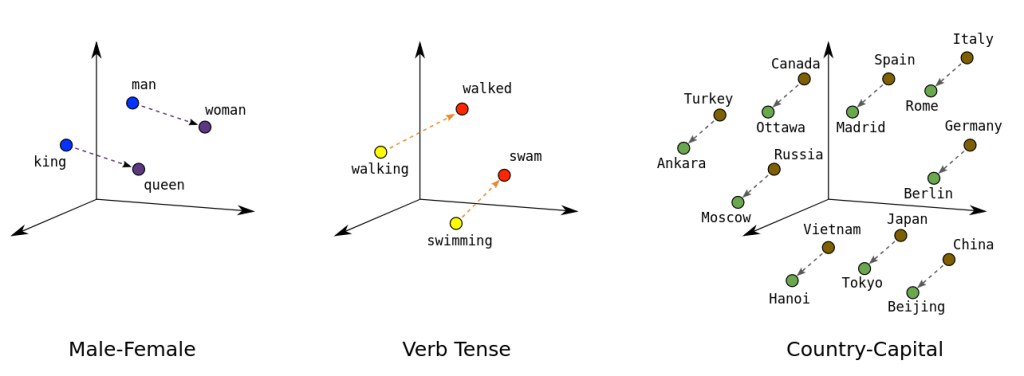

Now another shift is underway: from the internet as a place we go to an intelligence we bring to us. Generative AI reframes the web not as a destination but as a substrate for on-demand synthesis. Instead of clicking outward into a maze of links, we prompt, and the system composes a provisional text from learned patterns; a palimpsest of the internet, re-generated each time. In this sense, the interface transitions from navigation to conversation; from retrieval of artifacts to production of fresh, if probabilistic, prose.

What does this do to our rhetorical environment?

First, generative systems appear to restore hypotaxis, but of a different kind. Where the feed set items side by side (parataxis), AI models arrange them within a single, coherent utterance. Citations, definitions, warrants, and transitions arrive pre-braided, often with a competence that flatters the eye. Synthetic hypotaxis. Yet because the underlying process is statistical and unobserved, it risks performing coherence without guaranteeing evidence. The prose feels orderly; the epistemology may be wobbly. We are handed an essay when we might have needed a bibliography.

Second, generative AI re-centers dialogue as the controlling framework for knowledge work. Search terms give way to prompts, and prompts invite follow-ups, refinements, and counterfactuals. The standard unit of knowledge work becomes a conversation. This recovers something like the agility of oral exchange—call-and-response, iterative clarification—while living in a textual medium. In practice, this hybrid looks like scripted orality: improvisational yet instantly transcribed, searchable, editable, and archivable.

Third, the locus of authorship drifts. With the internet, we cited and linked; with AI models, we consult and compose. The user becomes a curator-designer, someone who specifies constraints, tones, examples, and audiences, while the model performs the heavy lifting of first-pass drafting and rephrasing. Our artifacts increasingly feel like bricolage: human intention wrapped around machine-generated scaffolds, tuned by promptcraft and revision.

Likely effects of the shift

Positive

- Acceleration of synthesis. Students and researchers can pull together working overviews in minutes, explore counterpositions, and translate among registers or languages. This lowers the activation energy for inquiry and can widen participation.

- Adaptive scaffolding. Models can perform as low-stakes tutors or writing partners, offering just-in-time explanations, outlines, and examples that match a learner’s current academic level.

- Access workarounds. For people blocked by jargon, gatekept PDFs, or unfamiliar discourse conventions, generative AI can paraphrase, summarize, or simulate genres they need to enter.

Negative

- Source erasure and credit drift. The move from links to syntheses obscures provenance. Without strong citation norms and tools, authority blurs and labor disappears into “the model.”

- Confident misstatements. Synthetic hypotaxis can launder uncertainty; tidy paragraphs can mask speculative claims (or hallucinations) behind elegantly connective prose.

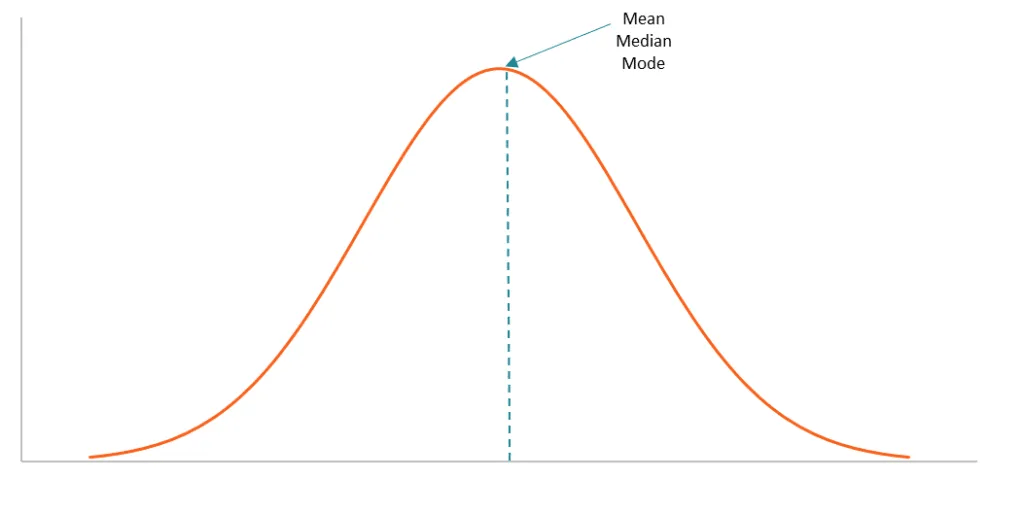

- Homogenization of style. Fluency becomes formulaic. If everyone leans on the same engines, we risk a median voice—competent, placid, and forgettable—unless we deliberately cultivate voice.

- Skill atrophy. If we outsource invention, arrangement, and revision too early or too often, we can lose the slow muscle of drafting, comparing sources, and building warrants from evidence.

Neutral/ambivalent

- New genres, new shibboleths. Prompts, system messages, and “prompt-sets” become shareable teaching artifacts; AI marginalia (notes explaining how output was shaped) may emerge as a norm. These could deepen transparency, or become ritual theater.

- Assessment realignment. If first drafts are cheap, assessment shifts toward process evidence (versions, notes, prompts), oral defenses, and situated tasks. This can improve authenticity but demands more from instructors.

- Attention economics. Conversation-first tools reduce tab-hopping, but they also reward rapid iteration. Some users will become more focused; others will live in an endless loop of “one more prompt.”

- Institutional enclosure. Organizations will build bespoke models and walled knowledge bases. That can improve reliability for local use while narrowing horizons and reinforcing house orthodoxies.

So what do we call this era?

If the internet cultivated networked parataxis, generative AI installs a layer of synthetic hypotaxis, or structured language on demand. I’m partial to naming it consultative literacy (to stress the dialogic nature), or generative rhetoric (to mark how invention and arrangement are becoming collaborative). Whatever we call it, the practical task is the same: pair the speed and plasticity of AI with disciplined habits of citation, verification, and style. In other words, keep the conviviality of the feed and the rigor of the page, and teach writers to orchestrate both.

The culture will follow the mode. As we move from going out into the web to inviting the web to speak through us, our work becomes less about locating information and more about shaping it: specifying constraints, testing outputs, insisting on sources, and cultivating voice. That is both the promise and the peril of an age where every prompt yields a fresh, provisional world.