We are enmeshed in data every day. It shapes our decisions, informs our perspectives, and drives much of modern life. Often, we wish for more data; rarely do we wish for less.

Yet there are moments when all we have is a single datapoint. And what can we do with just one? One datapoint offers almost nothing. It is isolated, contextless, and inert—a fragment of information without relationship or meaning. One datapoint might as well be no datapoint.

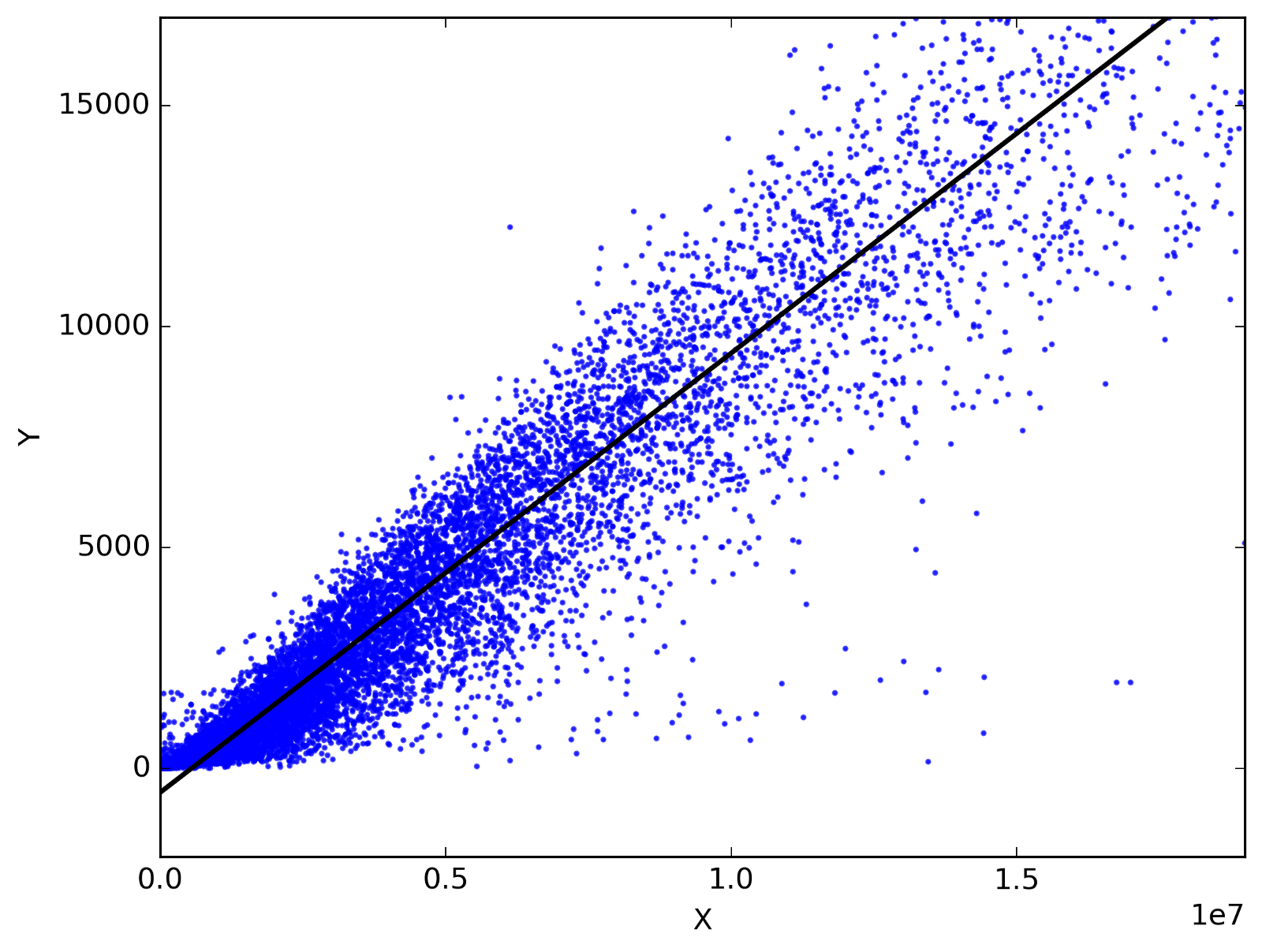

But two datapoints? That’s transformative. Moving from one to two is not just an incremental improvement; it is a fundamental shift. Your dataset has doubled in size, a 100% increase. More importantly, with two datapoints, you can begin to make connections. You can compare and combine, correlate and coordinate.

From Isolation to Interaction

Consider the possibilities unlocked by having two datapoints rather than one. A single name—first or last—is practically useless; it cannot identify a person. But a full name—two datapoints—suddenly carries weight. It situates someone in a specific context, distinguishing them from others and enabling meaningful identification.

The same holds true for testimony. A single witness to a crime might not provide enough perspective to reconstruct what happened. Their account could be unreliable, incomplete, or subjective. But with two witnesses, we gain a second perspective. Their testimonies can corroborate or contradict each other, offering a deeper understanding of the event.

Or think about computation. A solitary binary digit—0 or 1—cannot do much. It is a static state. But introduce a second binary digit, and the world changes. With two bits, you unlock four possible combinations (00, 01, 10, 11), the foundation of all logical computation. Every computer, no matter how powerful, builds its intricate systems of thought from this basic doubling.

The Exponential Power of Pairing

Why is the shift from one to two so significant? It is not simply the doubling of data, but the transition from isolation to interaction. A single datapoint cannot create relationships, patterns, or meaning. It is static. Two datapoints, however, introduce dynamics. They allow for comparison and combination, for movement between states, for a framework within which meaning can emerge.

This leap—from one to two—is the smallest step toward creating systems of knowledge. Science relies on comparisons to establish causality. A single experimental result is meaningless without a control group to measure it against. Literature and language depend on dualities—protagonist and antagonist, question and answer, speaker and audience. Even human vision is based on the comparison of binocular inputs, it is our two eyes that allow us to see depth.

AI and the Power of Two

The transformative power of n=2 is most recently demonstrated in the operation of generative AI. At its core, generative AI depends on the interaction of two distinct but interdependent datasets: the training data and the user’s prompt. The training data serves as the foundation—a vast repository of language patterns, structures, and examples amassed from diverse sources. This data alone, however, is inert; it is an immense collection of information without activation or direction. Similarly, a prompt—a fragment of input text provided by a user—is meaningless without context. It is a solitary datapoint, incapable of producing anything on its own.

When these two datasets combine, however, the true power of AI is unlocked. The training data provides a rich, multidimensional context, while the prompt activates specific pathways within that context, directing the AI to generate meaningful output. This dynamic interaction transforms static data into a creative process. Much like the leap from one to two datapoints, the relationship between the training data and the prompt enables the emergence of patterns, coherence, and utility. Without the prompt, the AI remains silent; without the training data, the prompt is purposeless. Together, they form a system capable of producing complex and contextually relevant language.

This relationship between training data and prompts underscores the profound significance of pairing, the power of n=2. The interaction between these two elements mirrors a broader principle: meaning arises not from isolation, but from connection. Just as two witnesses can construct a fuller account of an event, and two binary digits can enable computation, the union of training data and prompts enables AI to simulate human-like language and reasoning, creating systems that are both dynamic and generative. The leap from one to two here is not just a quantitative doubling—it is a qualitative transformation that makes the impossible possible.

Building Toward Complexity

Two is not the end point; it is the beginning. Once we have two datapoints, we can imagine three, then four, and so on, building increasingly complex systems. But we should not overlook the profound importance of the leap from one to two. It is the first and most crucial step toward understanding—toward the ability to identify patterns, make connections, and draw conclusions.

N=2 is the minimum threshold for meaning, the simplest structure capable of supporting complexity. From two datapoints, entire worlds of logic, creativity, and understanding can unfold.