The rise of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT has led many to believe we’ve entered an era of artificial general intelligence (AGI). Their remarkable fluency with language—arguably one of the most defining markers of human intelligence—fuels this perception. Language is deeply intertwined with thought, shaping and reflecting the way we conceptualize the world. But we must not mistake linguistic proficiency for genuine understanding or consciousness.

LLMs operate through a process that is, at its core, vastly different from human cognition. Our thoughts originate from lived experience, encoded into language by our conscious minds. LLMs, on the other hand, process language in three distinct steps:

- Text is translated into numerical data, where words and phrases are assigned numerical values based on probabilities.

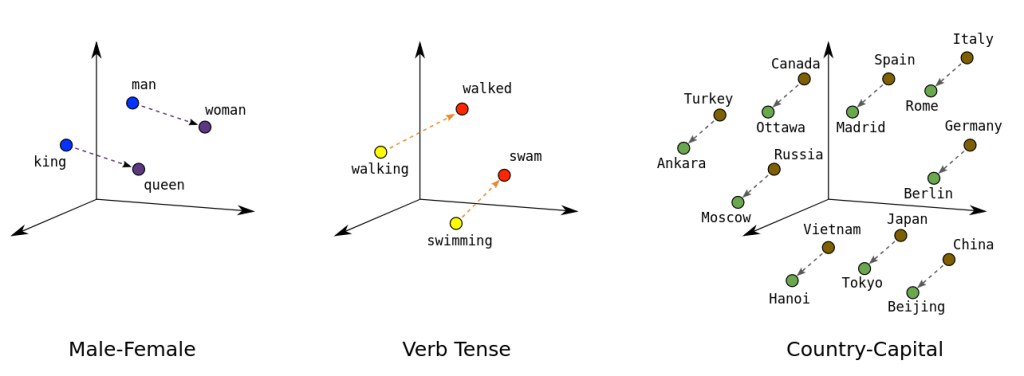

- These numbers are plotted within a vast multidimensional space, representing relationships between words.

- The model uses these relationships to generate new numerical representations, which are then retranslated into human-readable text.

This process is an intricate and compute-intensive simulation of language use, not an emulation of human thought. It’s modeling all the way down. The magic of such models lies in their mathematical nature—computers excel at calculating probabilities and relationships at scales and efficiencies humans cannot match. But this magic comes at the cost of true understanding. LLMs grasp the syntax of language—the rules and patterns governing how words appear together—but they remain blind to semantics, the actual meaning derived from human experience.

Take the phrase “public park.” ChatGPT “knows” the term only because it has been trained on vast amounts of text where those two words frequently co-occur. The model assigns probabilities to their appearance in relation to other words, which helps it predict and generate coherent sentences. Humans, by contrast, understand “public park” semantically. We draw on lived experience—walking on grass, seeing children play, or reading a sign that designates a space as public. Our understanding is grounded in sensory and conceptual knowledge of the world, not in statistical associations.

This difference is critical. What humans and computers do may appear similar, but they are fundamentally distinct. LLMs imitate language use so convincingly that it can seem like they think as we do. But this is an illusion. Computers do not possess consciousness. They don’t experience the world through sensory input; they process language data, which is itself encoded information. From input to output, their entire function involves encoding, decoding, and re-encoding data, without ever bridging the gap to experiential understanding.

To extend the analogy: a language model understands the geography of words in the way a GPS system represents the geography of the world. A GPS system can map distances, show boundaries, and indicate terrain, but it is not the world itself. It’s a tool, a representation—useful, precise, but fundamentally distinct from the lived reality it depicts. To say AI is intelligent in the way humans are is like saying Google Maps has traveled the world and been everywhere on its virtual globe; this is sort of true, in the sense that a decentralized convoy of Google cars equipped with cameras have indeed crawled the earth collecting visual data for Google street view, but is not literally true.

As we marvel at the capabilities of LLMs, we must remain clear-eyed about their limitations. Their proficiency with language reflects the sophistication of their statistical models, not the emergence of thought. Understanding this distinction is crucial as we navigate an era where AI tools increasingly shape our communication and decision-making.